Tough to Swallow: Understanding the Impact of the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis on Wildlife Poaching

*This is the first installment in our series Tough to Swallow, shedding light on the negative underbelly of wildlife poaching*

The inky black sky hung thickly across the dry savanna, dotted with a million tiny, glimmering stars and the dusty curvature of the Milky Way. A low hum of crickets and other insects filled the landscape with a symphony of sounds, the crescendo rising and falling to a beat all its own. The full moon, cartoonish and bright, asked confidently for attention through means of its sun-like beams. The South African desert was suddenly painted with shades of hunter green, and pacific blue, whispers of lilac and drops of charcoal black. Shining green eyes spotted everywhere, hiding above the plain grass and in-between tiny crevasses waiting patiently to strike. Like most creatures, the rhino would be resting peaceful until the dawn broke.

This scene was suddenly disrupted by stomping, but steady feet. The rust of a machete coating the hands of a slightly-frightened man, as he moved and milled around to the location where he last saw the very same rhino. Quickly, he saw the mottled grey skin and dull shine of a horn appear in the distance. That’s it. Game Over. A swiping move of the machete to the rhino’s face left a crimson hole, deep and discombobulated. Taking the precious horn in his hands and leaving a disfigured face in a trauma-filled panic. Both broken by the experience. Both will never be the same.

…

The poaching epidemic did not just happen overnight. Like all horrific things, a slow process of unraveling had to occur. The deadly combination of a faulty societal structure, and therefore a vulnerable population, has created somewhat of socio-political mess. South Africa, in particular, has a long and extensive history of colonialism. The country itself, rich in natural resources, has drawn hungry eyes to it’s fields for almost a century. And with the shaded hand of apartheid locking the country into rigid, race-based roles, it is obvious that inequality and prejudice would create vast difference in the population’s access to opportunities. Poverty is in fact directly, and indirectly, linked to the poaching crisis. A split between instant gratification and economic stability, versus long-term benefits to the environmental setting is the balance many in impoverished settings struggle with. While most poaching is done by illegal crime syndicates who trade precious animal goods on the Asian black market; it’s in turn fueled by poverty. Specifically, I believe this cycle can be micro-analyzed through the lens of the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis.

As a little bit of pretext, the financial crisis happened after a very economically stable period in South Africa’s history. The country had been going through somewhat of an economic boom after apartheid, even managing to create a budget surplus. Like most sub-Saharan African countries, manufactured goods, financial services, and the exportation of valuable natural commodities like gold and platinum fueled the pre-financial crisis economy. When the Global Financial Crisis hit, many believed that South Africa would be spared in the destructive collapse of global markets. In fact, the Minister of Finance Trevor Manuel argued that the country was impenetrable and blatantly refused to accept the inevitability of a recession. Slowly, the GDP fell almost 10% by 2009. The rippling effect of this created a dramatic rise in unemployment, officially around 25% but most speculate it was more like 32%. This rapid shift in the economy exposed many gaps in the fabric of South Africa as a country. No longer able to rest of laurels of pseudo stability, issues such as poverty, inequality, corruption, and previous withstanding levels of unemployment bubbled to the surface. The unemployment rate became one of the highest in the world, leaving more than one million people without any type of income. When unemployment is at such an elevated level, it can have dramatic social side-effects. One being discouraged workers syndrome, where workers lose all hope of ever finding a job in the current economic market. Specifically, when unemployment effects the younger demographic below the age of 35, risks of criminality and social instability increase greatly. This creates an environment in which individuals are highly more likely to take on a “whatever it takes” type of mentality.

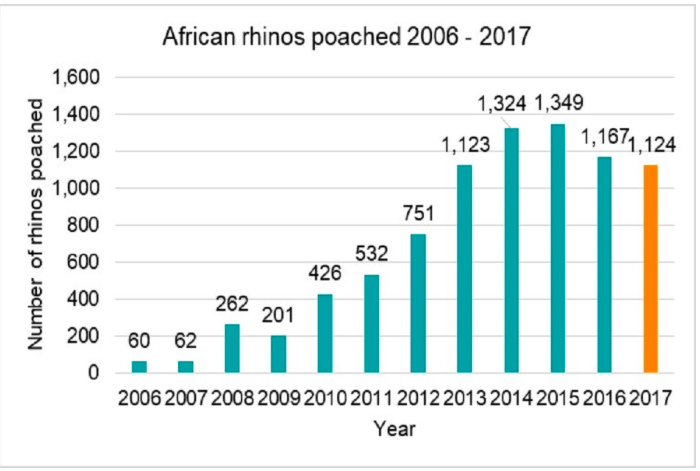

Below, this graph explains what poaching of South African rhinos has looked like over the most recent decade. With one of the largest rhino populations in the world, South Africa’s Kruger National Park has become a war-zone due to rampant poaching. As seen in the graph, a significant uptake can be seen in 2008, coinciding with the Global Financial Crisis and extreme unemployment.

*credits of this graph belong to savetherhino.org*

A helpful approach is trying to give the unemployed opportunities to get out of this trap. After the financial crisis, a massive effort was placed on trying to stimulate the job market and aid the jobless population. But remained a somewhat impossible problem to solve, even at one point having more of the population on government aid then paying yearly taxes. And with rhino horn going for around $60,000 US dollars a kilogram, it’s financial promises are significant.

When it comes to expelling poaching all together, theories of planned behavior are applied to understanding the psychology behind why one would attempt/succeed in poaching a precious animal. There is not a one size fits all approach to ending the process, as human behavior is always specific and individualized to circumstance. In the fight against poaching, there are two main areas that we can approach the problem from: eliminating the demand and uplifting surrounding communities.

Myths about the elusive medical properties of the horn have circulated for thousands of years, leading to claims that it can cure cancer and a myriad of other medical illnesses. This has been found to be untrue, and at it’s best, the horn can take the place of a weakened version of Advil. By dispelling rumors about the horn, and it’s inabilities to help anyone medically, the demand can slowly decrease.

In terms of uplifting the surrounding communities, allowing people to see another way out of their socio-economic class is incredibly important. Our group, Youth 4 African Wildlife recently helped a local Limpopo school by donating sanitary napkins to it’s girls of all ages. This was in an effort to ensure the young girls would not miss school because of their periods and continue to invest in their education. By supporting this local school and instilling the importance of education, we hoped to come at stopping poaching from a different angle.

The Global Financial Crisis did not start these issues, but exposed where South African as a society needed improvement. The issue of poaching is a multi-faceted, complex issue that not one person or group of people can solve alone. Only together, when we value our natural beings and our Mother Earth, at the same level we value the dollars in our pockets, will we see the actual change required to put this issue to rest.

Written and Photographed by Sophia Penelope Hill.